Recently, I came across a video by the comedian John Cleese talking about behaviourism. In it, he shared a joke—a man is looking for his key under a street lamp where there is light. Another man comes up to help him search for it. After searching futilely, the second man then asks the first if that’s where he dropped it. The first man then replies that he had dropped it in the dark alleyway yonder. John likens behaviourists’ attempts to understand human behaviour to the man’s misguided attempts to find his key1.

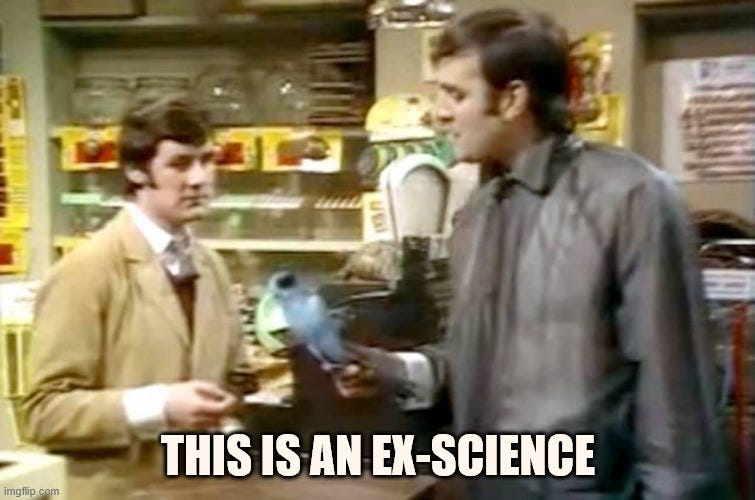

John is not alone. Behaviourism, as the popular consensus goes, is dead. It died in the wake of the cognitive revolution of the mid-20th century. Most introductory psychology courses preach this truth. Behaviourism is no more. It has ceased to be.

Well, not quite. Let me tell you why.

Points of Agreement

First, there are some things John said that I agree with and want to highlight:

[Scientists] tend to take parts of the problem that are very easy to do experiments on and then pretend those are the only ones that matter.

Indeed, we do. This is not unique to behaviourists. We find evidence of this across different disciplines. Case in point—well-being is extremely hard to define and measure. Thus, psychologists come up with questions like these

I am satisfied with my life.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

(strongly disagree) (strongly agree)

We pretend the numbers circled mean something real. When the score drops from 6 to 5 three months later, we also pretend that change means something real.

This ridiculously oversimplified idea that rats and pigeons can tell us all about the depth of the human condition.

Certainly, rats and pigeons cannot tell us all about the depth of the human condition. We’ve come a long way from that view. There are fundamental differences between humans and non-human animals, such as our sophisticated use of language and capacity for symbolism2. However, non-human animal studies can tell us a lot about ourselves. They have done so, and will continue to do so.

Scientists love doing science. They are sometimes remarkably uninterested in the philosophy of science.

It is entirely possible to have a scientific career without a grounding in a philosophy of science. I know this for a fact. More tragically, it is entirely possible to have a (distinguished) scientific career without creating any real-world impact whatsoever.

On The Scientific Method

While clever, I think the joke John shares misrepresents the workings of scientists. All analogies are imperfect, but here’s one that better approximates what scientists do.

Instead of trying to find a key on a patch of land, scientists seek to understand the lay of the land beyond our current established boundaries. Really, we are more like explorers and cartographers than what the Brits might call muppets or plonkers.

As to how we chart our paths through these unknown territories, it is perfectly reasonable of course to find the easy ways, the navigable paths, rather than hacking through brambles. Sometimes, these lead to dead ends, but there are always lessons to be gained from these journeys. Sometimes, we encounter new features (blimey, a lake!) that challenge our fundamental assumptions (there’s only land yonder) and force us to invent new technologies to progress further.

Broadly, we carry one of two types of flashlights on this mission. Some carry flashlights that cast a diffuse light over a large area, allowing us to observe a wider swath but with poorer fidelity. Others carry flashlights that produce concentrated narrow beams of light, allowing us to observe a smaller area very well. Behaviourists tend to fall into the latter category. Two very different methods, but both allowing us to gradually peel back more of the unknown.

On Behaviourism

What Behaviourism Isn’t

In talking about behaviourism, it is important to first be clear what we are referring to. Behaviourism is a philosophy of science, or more precisely, a group of related philosophical traditions. The philosophical tradition most non-behaviourists (including John) associate behaviourism with focuses solely on the relationship between environmental stimuli and observable behaviours.

Few behaviourists today embrace this position. Instead, most behaviourists believe that thoughts, feelings, and other internal processes are also things that we do, and thus behaviour. A full account of behaviour must include them.

What Behaviourism Is

Behaviourism centres on a core belief—our environments influence our behaviours, profoundly so.

A mother who scolds her child for misbehaving; a supervisor who calls attention to the outstanding work done by her supervisee; a judge who shows leniency to a hardened gangster after hearing about his rough upbringing; a school in an impoverished locality that provides free lunches to all its students—these are all people who have informally adopted a behaviourist worldview. According to this worldview, present outcomes shape future behaviours; past outcomes shape present behaviours. The psychologist Pat Friman calls it the circumstances view. Here’s him talking about this view.

To some, this view sounds remarkably unremarkable. Well, that’s just plain common sense, innit? Yet, this is not the dominant worldview. That worldview attributes the causes of behaviour to an individual’s personality, psyche, or some other innate quality. The child misbehaves because he has a flawed character. Gangsters commit atrocities because they are vile and evil. We take descriptive concepts and imbue them with explanatory powers3. For most of us, this is the default way of thinking, with the behaviourist worldview only surfacing occasionally.

In psychology, while behaviourism and its associated scientific practice (behaviour analysis) is no longer the dominant mode of enquiry, in many respects, its ideas have been successfully assimilated into mainstream thinking and practice. To understand behaviours, psychologists today observe observable behaviours (including self-reports using questionnaires). To change behaviours (including thoughts), excepting rare circumstances, we do so by changing environments. The psychologist Henry Roediger goes as far as to argue for the following possibility:

[Behaviourism] actually won the intellectual battle. In a very real sense, all psychologists today are behaviourists.

I’m not the president of the Association for Psychological Science so I won’t make similar bold claims. What I will say is that behaviourism and behaviour analysis has made significant contributions over the past decades and continues to do so. These aren't just theoretical abstractions, but practical successes that have improved millions of lives. To convince John of the value of a behaviourist worldview, here’s a list of 8 such contributions.

1. Alleviating Psychological Suffering

Therapies rooted in behaviourism are widely used in clinical settings to treat various psychological conditions. Behavioural activation is as effective as cognitive behavioural therapy (which also uses behavioural technologies by the way) in treating depression, at a much lower cost4. In recent years, we also witness the emergence of the “third-wave” of behaviour therapies, which are philosophically aligned with behaviourism. These therapies have been applied successfully to a wide range of conditions, including those previously considered untreatable5.

2. Teaching Skills to Individuals with Developmental Disabilities

Applied behaviour analysis is widely used in addressing skill deficits for individuals with profound disabilities, including cognition, language, social communication, adaptive, and daily living skills, and reducing severe problem behaviour which are exhibited by many of these individuals. Globally, there are currently more than 300,000 certified practitioners employing behavioural technologies to improve the quality of life of these individuals.

3. Building Quality Education Systems

Positive Behavioural Intervention and Supports (PBIS) is a tiered framework for improving learning, social, emotional, and behavioural outcomes in schools. PBIS favours teaching and reinforcing desired behaviours over punitive action for undesired behaviours, and provides different levels of supports based on the needs of each student. PBIS has been widely adopted, including in more than 25,000 schools in the US.

4. Supporting Positive Child and Adolescent Development

The Teaching-Family Model and Triple P – Positive Parenting Program are examples of programmes that support families and caregivers in raising children successfully. They are person-centred, strengths-based, cost-effective programmes drawing from behavioural principles to support child and adolescent development, including those who have experienced trauma, abuse, and loss. These empirically supported (see here and here) programmes have benefited millions of children, adolescents, and their families/caregivers to date.

5. Treating Addictions

Turns out, one of the most effective ways to stop individuals from abusing drugs is simply to pay them not to. This method, known as contingency management, has been around for decades, but has not been adopted widely, mainly due to ethical concerns—as the dominant worldview would argue, why should we pay them to do the right thing? However, with robust evidence for its effectiveness, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness, contingency management programmes are increasingly being implemented.

6. Enhancing Employee Performance and Workplace Culture

Behavioural principles have been applied to the workplace to help organisations meet their goals. Such work, termed organisational behaviour management, involves developing or improving processes to enhance employee performance, employee retention and satisfaction, creating optimal workplace cultures, and improving quality standards. This is highly important. Many organisations have incredibly toxic workplace cultures, and their leaders read bestsellers that make claims with zero empirical basis and covertly believe in rank and yank practices6.

7. Improving Workplace Safety

One particular application of behavioural principles in the workplace is in safety improvement, especially in environments with high occupational health risks. Behaviour-based safety (BBS) involves systematically tracking and improving safety-related behaviours in such environments. In some cases, the effects of BBS initiatives have been shown to persist even 14 years later.

8. Improving Decision-Making

Folk psychologists have it that delayed outcomes has less bearing on our behaviours than immediate outcomes. And they are right. I’ve written about this in a previous article.

Thanks to decades of research, we now know precisely how so. The difference in subjective value between an outcome today vs. a week from now is much greater than between 10 years vs. 20 years in the future. These insights have allowed us to develop methods to help individuals make better choices, including some pretty interesting ones. Similarly, we also know a lot about how people make choices with probabilistic outcomes.

BONUS: Advancing Artificial Intelligence

One of the major catalysts for the cognitive revolution was the advancement of computer technologies, creating the metaphor of the brain as a computer and the mind its processes. And so it is with supreme irony that many advances in artificial intelligence today are deeply inspired by behaviourism. I will probably do a deep dive on artificial intelligence and behavioural science sometime in the future, but for now here are two examples:

How do you teach a computer agent to play games or drive a car? Well, you would first establish what are good and bad outcomes—increase/decrease win probability, increase/decrease successful commute (without killing anyone) probability—then run simulations and allow these outcomes to shape the agent’s behaviours. Do this enough, and we get highly sophisticated agents that can perform feats of miracles, such as this7:

When using ChatGPT or any other Large Language Models, occasionally, you may see it provide two responses to your prompt and ask you to select the one you prefer8. For example, you provide a picture of a bird and ask, what is this? Answer A: It’s a bird. Answer B: It appears to be a Satanic Goatsucker. These birds are found in… Your feedback goes into training the next generation of models, thus shaping their future output.

The Profound Missed Stakes

In many ways, we live in the most behaviourally engineered world that has ever existed. We know more about influencing behaviours than ever before. With this knowledge, we can help individuals eat better, save more, treat others more kindly. We can also make them eat worse, spend more, and turn them against each other. All these achieved through subtle manipulations in the individuals’ environments, possibly without their notice.

In his article, Roediger predicted that a strong form of behaviourism would make a comeback in mainstream psychology in this century. In many ways, it already has.

To John and my readers, I hope to have convinced you of that behaviourism is alive and thriving (albeit with a few flesh wounds).

But in truth, the label hardly matters. What matters is pursuing a psychological science that helps us understand and solve our greatest challenges, whatever we decide to call that. Whether a behaviourist worldview brings us closer to that goal, I’ll let you be the judge.

It’s more chic for behaviourists to call ourselves behaviour analysts these days.

In fact, not all we’ve learnt from rats transfer to let’s say, goats.

Example: We observe Michael’s behavioural tendencies—avoidance of crowded areas, preference for solitary activities, scoring tendencies on personality questionnaires—and label him an introvert (used as a description). When asked why Michael doesn’t turn up for the party, we say well, you know he’s always been quite the introvert (used as an explanation).

Behavioural activation involves increasing contact with positive and rewarding activities/environments. That in turn influences what we do, and what we think and feel (surprise, surprise), thus ameliorating many of the symptoms of depression.

Examples of “third-wave” therapies include acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behaviour therapy, process-based therapy, and functional analytic psychotherapy.

Rank and yank, or stack ranking, refers to a system where the top performing employees are rewarded while the bottom performing employees are fired. As you might imagine, such practices are absolutely detrimental to workplace collaboration.

I’ve promoted this documentary in a previous article, but it’s just so damn beautiful.

I spent around 10 mins trying to get ChatGPT and Claude to provide an example but they refused to cooperate. Oh well.

Very nice rebuttal. I remember when that came around, and shaking my head at the ongoing misrepresentations of behaviorism, but this one had an extra punch, coming from one of my comic idols. And in fact, the story is one I used to tell in lectures - though for a different reason, that science has to start somewhere - why not start where the light is good.? Anyway, very nice job of educating folks about behavior analysis, and the differences between folk/lay psychology and real behavioral science. Well done!

This was an excellent rebuttal. All the major points made: the circumstances view is the widely held view but not the one in which most professionals operate; vast generality, we contribute across disciplines; the adoption or absorption of some of our concepts by other types of psychologists and others; and how it doesn’t matter what you call it but focusing on changing behavior by changing the environmental contingencies is the way! Loved this.

Oh, and I loved the Monty Python reference. 😆 If you aren’t on the teaching behavior analysis (TBA) listserv, it’s a funny coincidence that you used that reference. When the Cleese video was sent around a few weeks ago, I asked what the best reply would entail, and someone said, “Tis but a flesh wound.” Great minds, I suppose.

Anyway, thanks again. This was great.