What's In A Nudge? Part I

Published 15 years ago, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s (henceforth T&S) bestseller Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness ushered in a new era for the behavioural sciences. In its aftermath, behavioural science teams (colloquially called Nudge Units1) began springing up in various countries and organisations, contributing greatly to addressing many socially significant issues. The book itself was a commercial success, thrusting the behavioural sciences, particularly Nudge Theory, into the public spotlight2. If you are reading this article, you probably already have at least a passing familiarity with nudges.

As a population health researcher, the word nudge pops up often at my workplace. And understandably so. We’re in the business of changing (health) behaviours. Health outcomes are inextricably linked to behaviours—an individual’s health is directly impacted by their behaviours, and a population’s health is a function of its systems, which are themselves products of interlocking behaviours of individuals within the systems. Trouble is, no one seems to have a concrete grasp on what a nudge really is. Rather, it is most often used as a generic catch-all for a broad, unspecific collection of processes for changing behaviours.

We can hardly blame them. The immense success of T&S’s book resulted in nudge entering the everyday lexicon, diluting its original meaning.

As psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer notes,

Since the publication of Nudge, almost everything that affects behaviour has been renamed a nudge, which renders this concept meaningless.

Spoiler alert: I agree with Gigerenzer. Without precision and clarity, the concept lacks explanatory power—it pretends to explain a behaviour change process without really doing so. As we shall see, even its original meaning as defined by T&S leaves room for plenty of questions.

In Part I of this two-parter, we unpack Nudge Theory and attempt to operationally define a nudge. This will set the stage for understanding the types of BCTs that are claimed to be nudges in Part II. Let’s dive in.

What is Nudge Theory?

At the risk of increasing confusion, I should first caution that there isn’t a consensus definition of a nudge, with some even arguing that nudges should be three separate concepts. This is due in no small part to its initial conceptualisation by T&S, which aimed to integrate several themes into a coherent theory. For T&S, a nudge

serves as an operational definition for a collection of BCTs (many of which existed well before nudge was coined) that are conceptually linked in some way,

is predicated on an assumption that humans fail to behave rationally, with nudges serving to either remediate these rationality failures, or exploit these rationality failures to change behaviours,

is the primary tool for achieving libertarian paternalism, an ideology that deems it possible to influence behaviour positively without limiting freedom of choice—seemingly resolving the tension between the opposing ideologies of libertarianism (maximising freedom of choice) and paternalism (restricting freedom of choice, often for the individual’s “own good”).

In short, Themes 2 and 3 serve as a theoretical framework underpinning nudges (Theme 1). A critique of Themes 2 and 3 goes beyond the scope of this article. For the interested reader, I recommend these 2 papers (here and here). For our purposes, it should be noted neither Themes 2 or 3 are necessary or sufficient conditions for many of the BCTs described as nudges (Theme 1). To briefly illustrate,

Not all BCTs described involve rationality failures (if we can even agree on what rational behaviour is). With the oft-cited nudge example of painted-on flies in urinals to reduce spillage, it’s certainly a stretch to claim yup, men aim poorly because they are irrational.

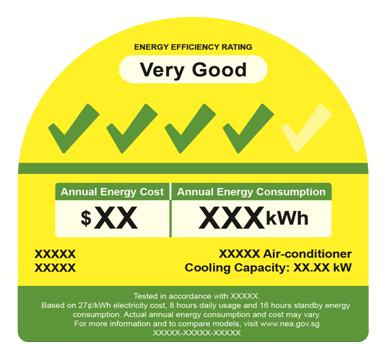

Urinal with painted-on fly. Wikimedia Commons Another nudge-type BCT is to provide information to individuals about the choices available to them. For example, many appliances in Singapore come with an energy label that contains information about the annual expected energy consumption, cost, and an energy efficiency rating. These stickers guide individuals toward making cost-effective (and climate-friendly) choices. The assumption here is that individuals lack information, not rationality.

Energy label template found on certain appliances in Singapore. National Climate Change Secretariat Singapore Not all BCTs described necessarily meet the conditions for libertarian paternalism. A signature nudge-type BCT is the use of defaults, or a pre-set choice if the individual does not do anything3. One of the biggest success stories for nudge proponents is the use of opt-out organ donation defaults (citizens are presumed organ donors unless they explicitly withdraw their consent) in various countries (including here in Singapore), greatly increasing the organ donation consent rate. However, if you were to survey random passers-by on the streets of Singapore, you would be surprised by how many are unaware that they had consented to donating their organs. The use of such defaults bypasses the individual’s actual choice, and cannot be said to meet the conditions for libertarian paternalism, except in the most liberal sense of the phrase. Indeed, recent evidence (here and here) seems to suggest there is minimal difference in actual organ donation rates in countries that adopt opt-out vs opt-in (citizens must explicitly consent to become organ donors) defaults despite the difference in consent rates, an indication that opt-out defaults probably created artifically inflated consent rates.

For now, let us disentangle nudges from their troubled theoretical framework. In the next sections, we will attempt to operationally define a nudge.

What is a Nudge?

To begin, let us examine the definition provided by the OGs in their book:

A nudge is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. [emphases mine]

Let’s reword that in plain English. To be considered a nudge, three conditions must be satisfied:

The context is intentionally altered to influence choice

The number of choices available is not restricted

The outcomes of those choices are not significantly altered

Let’s examine each condition in greater detail.

Deconstructing T&S’s Definition

1. Intentional Context Alteration

Choosing is behaviour, and it does not occur in a vacuum. It can only be understood in the context it is situated within. There are two aspects to understanding behaviour in context4. First, as previously written, outcomes select behaviour—choices tend to correspond with the best available outcome. Second, stimuli that predict these outcomes become important to us—they act as signals that guide us toward or away from these outcomes (we will refer to these as antecedents). These can be events or features in our environment, or our thoughts, feelings, and sensations. Crucially, antecedents are only relevant to us if they predict important outcomes—that is, they gain their power to influence behaviour through their associated outcome. Installing a recycling bin in a lift lobby can increase recycling of climate-conscious individuals, but will have little effect on those who are indifferent to climate change5.

In evaluating choices, we are constantly looking for such signals to guide our choices. Here’s an example provided in T&S’s book. Imagine you are suffering from a serious heart condition, and the doctor proposes an operation. When you enquire about the odds of survival, she says:

“Of 100 patients who have this operation, 90 are alive after 5 years.”

In an alternate universe, the doctor skipped her morning coffee and is feeling particularly sullen. She says instead:

“Of 100 patients who have this operation, 10 are dead after 5 years.”

You will be quick to realise that these two sentences are mathematically equivalent. However, the way each statement is framed signals very different outcomes. Unsurprisingly, individuals presented with either statement choose quite differently.

It is important to emphasise that this condition encompasses the entire universe of BCTs and even regulations, which most don’t think of as behavioural in nature (of course they are) and does not distinguish nudges from non-nudges. Here’s where most people get it wrong. To be considered a nudge, Conditions 2 and 3 must also be satisfied.

2. Choice Preservation

At first glance, this condition is straightforward. If we don’t restrict choices, we are good. But what does that truly mean?

There are 2 possible ways of thinking about this. First, choices are not concealed from the individual. If one were looking to influence food delivery app users to order healthier options, completely removing the fast-food options would violate this condition. Showing the healthier options first, followed by the fast-food optios would not. Better still, we can place the fast-food options in a separate tab requiring an additional response to access (e.g., clicking on a see more button). Of course, the more hoops one must jump through to access the fast-food options, the less clear it is that this condition is satisfied.

Second, choices are not restricted by coercion or aversive control through imposing costs substantial enough to influence behaviour. Most would agree that a total smoking ban would clearly violate this condition6. Creating and demarcating smoking and no smoking zones within a district would not. Again, as it becomes harder to access a choice, we become less certain that the condition is satisfied. If designated smoking zones are a short walk away, smokers might feel that their choice is not restricted. I have to walk an additional 5 mins to smoke, that’s fine. It’s probably good for me too. What if they had to walk 10 mins, or 20 mins, or 30 mins to the nearest designated smoking area? At what distance can we agree that the degree of inconvenience is effectively a restriction?

3. Outcome Neutrality

First, we should clarify that T&S used the term economic incentives rather than outcomes. For some, economic incentives can be narrowly defined as financial incentives or costs. Fines for smoking are precluded. Invoking social disapproval for smoking is fine (haha).

Even so, many (including the OGs themselves) still refer to interventions that directly programme financial incentives/costs as nudges. In their book, T&S describe a “dollar a day” programme, in which teenage girls already with children are paid a dollar for each day they are not pregnant. T&S also describe a cap-and-trade system to reduce greenhouse gas emission, in which companies who pollute below a threshold (the “cap”) are allowed to sell their remaining emissions rights (the “trade”) to companies who pollute more. This creates a financial incentive for companies to pollute less as they can profit by trading their remaining emission rights.

That said, narrowly defining economic incentives as those that involve financial gains/losses fails to acknowledge the diverse range of outcomes that influence behaviour, of which financial incentives are but one. For many, experiencing social disapproval can be more aversive than getting a fine, and some would readily pay to avoid such experiences. T&S acknowledged as much, stating in a footnote in their book:

Alert readers will notice that incentives can come in different forms. Some of our nudges do, in a sense, impose cognitive (rather than material) costs, and in that sense alter incentives.

A second less easily resolved issue in the wording is the inclusion of the word significantly. What counts as a significant incentive/cost? In the same footnote, T&S added:

Nudges count as such, and qualify as libertarian paternalism, only if any costs are low.

Obviously, in modifying the outcomes, if the incentives/costs are too low, the likelihood of influencing behaviour is minimal. No (or very few) smoker will quit if you pay them a dollar for each month they abstain from smoking. So, the change in outcomes must be in a sense, significant enough to influence behaviour, but not too significant.

In terms of providing incentives, one might say the “dollar a day” programme qualifies as a nudge as the monetary gain is trivial. However, a cap-and-trade system for sulphur dioxide in the US has led to estimated cost savings of US$700–$800 million annually on the back of strong financial incentives for companies to pollute less.

When looking at costs, with our smoking zones example, what travelling distance to the nearest smoking zone would be a low cost? At what point along the continuum can we distinguish a nudge from a ban?

We either accept that nudges include changing outcomes, and navigate those fuzzy boundaries, or limit nudges solely to BCTs that influence behaviours through altering the antecedent context.

Towards an Operational Definition

At this point, you might be feeling more confused than ever. Weren’t you supposed to provide clarity? you ask. First, take a deep breath. We’ll get through this, I promise.

In analysing the 3 nudge conditions proposed by T&S, we realise that they occasion more questions to be answered. For us to continue, some simplification is in order. In keeping with an interpretation broadly compatible with both T&S’s definition and a selectionist view, we will adopt a definition proposed by behavioural scientists Carsta Simon and Marco Tagliabue:

Nudging focuses on the role of antecedents of behaviour when analysing choice architecture. Changes in choice architecture referred to as nudging, do not program changes in consequences.

In this definition, the antecedent context is altered (Condition 1) but not outcomes of behaviours (Condition 3, partially), thus avoiding the use of coercion or imposing costs to restrict choice (Condition 2). To avoid troubles with determining what incentives/costs are acceptable for nudge-type BCTs, we will conveniently omit all BCTs that involve programmed changes to outcomes, whether financial or otherwise.

In summary, we began with an overview of Nudge Theory. We jettisoned its troubled theoretical framework and focused on the nudge concept. We scrutinised the 3 conditions contained within T&S’s definition and examined some of its conceptual issues. Finally, we proposed a new definition that keeps to the spirit (we hope) of T&S’s definition, but offers better clarity.

Armed with our refined definition, we are finally ready to evaluate actual nudge-type BCTs, which we will do so in Part II. We will also evaluate the evidence for their effectiveness, and discuss the role of nudge-type BCTs in a behavioural scientist’s toolbox. Stay tuned.

Examples of Nudge Units include the Behavioural Insights Team, ideas42, and eMBeD. Many government agencies and organisations have also started developing their own internal Nudge Units. Here in Singapore, there are at least 8 government agencies with their own behavioural science teams.

In many ways, both Nudge and Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow had a huge influence on me personally. As a dreamy undergraduate, these books lit me up in a way that memorising basic psychology concepts did not. RIP Danny.

The word default and its derivations appears 183 times in the first-edition of Nudge.

A third aspect we have to consider is the individual’s evolutionary past and learning history. For the purposes of this article, we will conveniently omit this discussion.

Or those climate change deniers might recycle more to avoid dirty looks from others in the lift lobby. In this case, the relevant outcome is social pressure and the relevant antecedents the recycling bin AND the presence of others.

Technically, the individual can still smoke (unless they were physically restrained), so the choice is not really restricted. However, by imposing costs, we reduce the likelihood of the individual making that choice.

Fantastic piece--cannot wait for Part 2!